Introduction Spanish cob coinage represents a fascinating chapter in numismatic and economic history. Cobs, derived from the Spanish phrase “cabo de barra” meaning “end of the bar,” (cobs were sliced from silver bars) were hand-struck silver and gold coins produced by Spanish colonial mints in the New World from the 16th to 18th centuries. Despite their often crude appearance, cobs served as an important global currency, fueling Spain’s empire and spreading throughout the world via trade. The story of cob coinage – from the establishment of the first New World mint in Mexico City in 1536 to the final Potosí mint cobs struck in 1773 and the persistence of the cob design in Latin America into the early 19th century – chronicles Spain’s golden age as a colonial power and its lasting influence on the Americas. It also sheds light on the economic, political, and technological forces that shaped the evolution of money itself during this pivotal period in history.

The birth of the cob – responding to a silver boom The first Spanish colonial mint opened in Mexico City in 1536 after silver mines were discovered in Mexico in the 1530s, with silver cobs (known as “reales”) among the first coins produced. One early example is this Mexican colonial Felipe II King of Spain 1556-1598 AR 8 Reales featuring a simple cross and lions and castles design, typical of the earliest cobs:

This early Mexican cob (also known as “macuquinas”) demonstrates the somewhat crude and non-uniform nature that would characterize cobs throughout their history. The cross is slightly off-center, the castles and lions are barely discernible, and the coin is an odd shape. These imperfections were largely a result of the manual striking process and the varying skill levels of mint workers, rather than an intentional design choice. The primary goal was to quickly turn silver into coin while still bearing recognizable symbols of the Spanish crown.

This is a contrast between the well-designed European coins such as the 1546 round 1 Real coin of Charles I (1535-1556) issued in Mexico seen here:

The more crudely produced cobs illustrate the evolving priorities of the Spanish Empire in its American colonies. While early coins reflect a continuation of European minting traditions and an emphasis on royal symbolism, the practical demands of managing an empire built on precious metals led to the development of the cob coinage system. This system was characterized by its efficiency and practicality, at the expense of the aesthetic qualities and uniformity that were hallmarks of earlier issues.

The rudimentary design and manufacture of Colonial Cob coinage, especially when contrasted with the more sophisticated and finely detailed coins minted during the reign of Philip III of Spain (1598-1621), can be attributed to a combination of factors stemming from their intended use, production context, and the limitations of colonial resources. Cobs were primarily minted for international trade within the New World colonies of Spain, valued for their metal content rather than appearance, facilitating quicker production to satisfy the demands of trade across the Americas and Asia. This focus on expedient mass production meant that the coins often bore irregular shapes and partial designs, a result of the simplistic hand-hammering method used in their creation. In Spain, coin aesthetics might have reflected the monarchy’s prestige, whereas colonial coins were pragmatic economic tools, with aesthetics taking a back seat. The colonial mints, constrained by the available equipment, skilled labor, and the pressing need to circulate silver and gold, opted for efficiency over craftsmanship. Furthermore, the irregularity of cobs offered a practical advantage by being less susceptible to counterfeiting and clipping, practices that could undermine the currency’s value. This emphasis on functionality and production efficiency over aesthetic or symbolic value resulted in the characteristic rudimentary nature of Colonial Cob coinage, showcasing the Spanish Empire’s logistical and economic priorities in its colonial endeavors over the more meticulous craftsmanship typical of coins intended for domestic or European use.

It was the discovery of the massive silver deposits at Potosí (in modern-day Bolivia) in 1545 that kicked off a silver boom and rapid expansion of Spanish colonial minting. The Potosí mint opened in 1574 and would go on to produce the majority of the world’s silver coinage over the next two centuries. Here is an example of a 2 reales cob from the Potosí mint from the 1600s:

This Potosí cob, while slightly more uniform in shape than the earlier Mexican example, still shows the somewhat crude, uneven strike and off-center design that made cobs fast to produce but occasionally problematic in circulation.

With huge amounts of silver flowing in, the priority was to quickly turn it into coins to ship back to Spain. Each cob was hand-struck and unique, but met the specified weight for the denomination.

Unfortunatly, numerous Spanish cobs were consigned to the depths of the ocean due to their pivotal role in the extensive global trade networks spanning the 16th to 18th centuries, primarily involving the transatlantic transportation of immense quantities of silver and gold from the New World back to Europe. This high frequency of maritime misfortunes can be attributed to a series of factors: the Spanish Empire’s heavy dependence on sea routes to move its colonial wealth, the organization of treasure fleets laden with precious metals and goods which were prime targets for pirates and privateers, and the perilous nature of these voyages that faced the threats of adverse weather, including hurricanes and storms notorious in the Caribbean and Atlantic passages. Moreover, the era’s navigational challenges and potential human errors posed significant risks, alongside the prevalent warfare and piracy that could lead to violent confrontations and the sinking of ships. An additional hazard was the common practice of overloading vessels to maximize cargo, compromising their maneuverability and increasing their vulnerability to sinking when faced with inclement weather or damage. The cumulative effect of these factors led to the loss of countless ships over the centuries, each carrying cobs and other treasures to the sea floor. Today, the discovery of these shipwrecks by treasure hunters and archaeologists continues to unveil invaluable insights into historical global trade dynamics, maritime technology, and the economic strategies of the Spanish Empire, with the recovered coins and artifacts cherished by collectors and historians for the tangible connection they provide to our shared past and the intricate web of commerce that once spanned the globe.

Note: Determining saltwater damage on Spanish cobs or other submerged coins involves examining for signs such as surface corrosion, characterized by pitting and the corrosive action of saltwater that eats away at the metal. Encrustations from minerals, sand, and other oceanic deposits, along with color changes that result in darkened tarnish on silver and dullness on gold, are also telltale signs. The fine details and motifs on the coin may show wear or erosion, indicative of the abrasive effects of sand and salt, while the presence of metal fatigue, such as cracking or flaking, suggests the structural integrity of the coin has been compromised. While assessing a coin for saltwater damage, it’s essential to consider its provenance and the combination of these indicators, as they not only affect the coin’s condition and value but also contribute to the historical significance, especially if the coin is from a known shipwreck, adding a layer of narrative to its existence.

Shipwrecks:

- The Atocha (1622): Perhaps the most famous of all, the Nuestra Señora de Atocha was part of a Spanish fleet caught in a hurricane off the coast of Florida. Laden with a vast cargo of gold, silver, and precious gems from the mines of Peru and Bolivia, the Atocha sank near the Florida Keys. Its discovery in 1985 by treasure hunter Mel Fisher and his team uncovered an immense treasure of gold and silver cobs, along with other valuable artifacts, making headlines worldwide.

- The 1715 Spanish Treasure Fleet: This fleet of eleven ships was returning to Spain from Havana, loaded with gold, silver, and jewels from the New World when it encountered a hurricane off the coast of Florida, leading to the loss of all the ships near present-day Vero Beach. Over the years, various portions of the fleet’s treasure, including thousands of silver cobs, have been recovered, contributing to the lore of the Treasure Coast.

- The San José (1708): The San José was a Spanish galleon sunk by the British navy off the coast of Cartagena, Colombia, during the War of Spanish Succession. It was carrying gold, silver, and emeralds from the mines of Peru and Bolivia to finance the Spanish war effort. In 2015, the Colombian government announced the discovery of the wreck, which is believed to contain one of the most valuable treasures ever lost at sea, including substantial quantities of gold and silver cobs.

- The Capitana (1654): Also known as the Jesús María de la Limpia Concepción, the Capitana was the flagship of the South Sea Fleet when it struck a reef and sank off the coast of Ecuador. It was heavily laden with silver cobs minted in Potosí. Modern recovery efforts have yielded significant finds of these coins, offering a glimpse into the wealth Spain extracted from its American colonies.

- The Consolación (1681): After being attacked by pirates, the Consolación was intentionally run aground on Santa Clara Island (also known as Isla del Muerto) near Ecuador to prevent its capture. The ship was carrying a large cargo of silver cobs from the Potosí mint. Modern salvaging operations have recovered part of its treasure, further contributing to the lore of lost Spanish wealth in the New World.

Initially, cobs were produced in denominations of 1, 2, 4 and 8 reales starting in 1572 under King Philip II. The largest silver cob, the 8 reales, would come to be known as the “Spanish dollar” and “piece of eight,” gaining wide acceptance as a global trade coin. A 1/2 real was added in 1607.

The weights of Spanish cobs varied depending on the denomination and the specific time period during which they were minted. Cobs were issued in several denominations, including but not limited to the 1, 2, 4, and 8 reales for silver cobs, and 1, 2, 4, and 8 escudos for gold cobs. The target weights for these coins were based on the Spanish monetary system, which was theoretically standardized but could vary in practice due to the rudimentary minting process and the challenges in controlling the exact weight of each coin.

Silver Cobs

- 1 Real: approximately 3.38 grams

- 2 Reales: approximately 6.77 grams

- 4 Reales: approximately 13.54 grams

- 8 Reales (also known as the “Piece of Eight”): approximately 27.07 grams

Gold Cobs

- 1 Escudo: approximately 3.38 grams

- 2 Escudos: approximately 6.77 grams

- 4 Escudos: approximately 13.54 grams

- 8 Escudos (also known as the “Doubloon”): approximately 27.07 grams

It’s important to note that these weights are ideal targets. In practice, the weight of individual cobs could vary significantly due to the manual methods used in their production. The cobs were hand-struck and often irregularly cut from silver or gold bars, leading to variations in both weight and shape. This variability was somewhat tolerated because the value of the cobs was primarily based on their precious metal content rather than their face value or appearance.

Mints in the Spanish colonies operated under the authority of the Crown but faced challenges in maintaining strict control over the coinage standards, leading to variations in weight and quality among cobs from different mints and time periods. Over time, attempts were made to standardize coin weights and improve the minting process, but the unique characteristics of cobs remained until the transition to machine-struck (milled) coinage in the 18th century, which allowed for greater uniformity and precision in coin production.

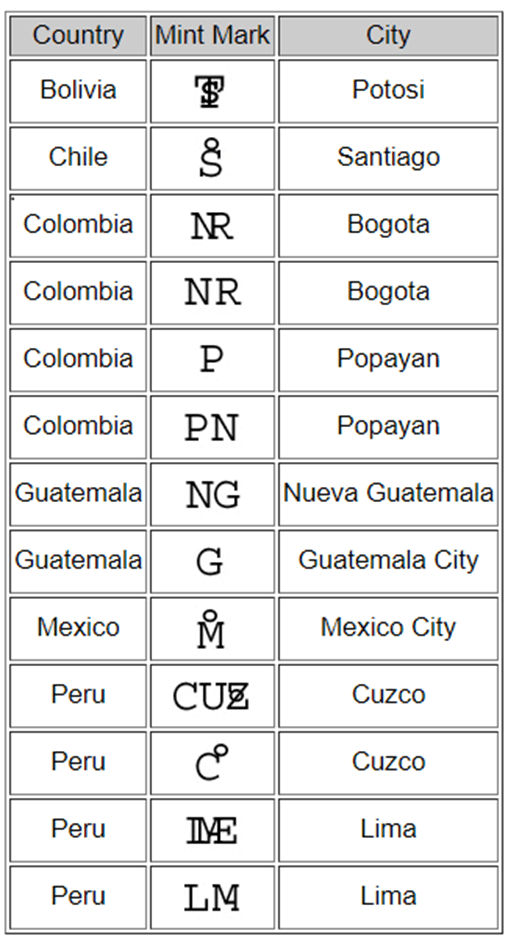

From the 16th to 18th century, Spanish colonial mints in Mexico, Peru, and Colombia churned out vast quantities of silver and gold cobs that flowed throughout the world, spreading the economic influence of the Spanish Empire. Here is a list of the common mints:

Bolivian cobs struck at the Potosí mint, like this 2 reales from 1668, were particularly important in global trade:

This Potosí cob displays the standard features of mid-late 17th century cobs – a shield with the Hapsburg coat of arms on one side, and a cross with lions and castles on the other. The assayer’s initial (E) and the denomination (2) flank the shield. While the designs are clear, the strike is uneven and the shape is far from round – hallmarks of the cob style.

Potosí and Lima (opened 1568, modern-day Peru) together accounted for over 80% of the world’s silver production in the late 16th century. Potosí alone produced an estimated 60% of all silver mined in the world between 1574 and 1773.

Cobs were used for transatlantic trade with Europe as well as trade with Asia via the Manila Galleons that crossed the Pacific from Acapulco, Mexico to Manila, Philippines starting in 1565. In Asia, cobs were often counter stamped with Chinese characters called “chop marks” that vouched for their silver content and authenticity. These chop-marked cobs are particularly prized by collectors today as they tell a story of the coins’ global journey and acceptance as world currency. Here is a Mexico City cob 8 reales from 1652, with chop-mark as from circulation in Asia:

Although cobs were meant to be melted down and re-coined upon reaching Spain, many continued circulating, with silver cobs gaining a reputation as a reliable trade currency as far away as the English colonies in North America and the Caribbean. Here is a set of Colombian 4 reales cobs from 1655 (assayer S below mintmark C to right) that may have seen circulation in the West Indies:

These 4 reales cobs were produced at the Cartagena mint (opened 1622 in modern-day Colombia). It features the distinctive “pillars and waves” reverse design introduced in the mid-1600s at the Peruvian and Colombian mints. The Cartagena mint primarily produced gold cobs, but also issued silver in smaller quantities.

Cobs were the “pieces of eight” and “doubloons” of pirate legends. However, their crude style made them susceptible to clipping and counterfeiting. The Potosí mint in particular developed a poor reputation after scandals in the early 1600s involving corrupt assayers who were debasing the silver.

In 1648, an assay in Spain determined that some Potosí issues were more than half copper, The scandal reached its peak towards the end of that decade, leading to a trial, conviction and execution of Felipe Ramirez de Arellano in 1650 for fraud against the Crown and to serve as an example against further nefarious activities at the mint.

Note: A coin assayer is often assigned to each mint or assay office to determine and assure that all coins produced at the mint have the correct content or purity of each metal specified, usually by law, to be contained in them. Here is a list of Assayer marks from Mel Fisher’s website.

Evolution of cob designs To combat counterfeiting and restore confidence, cob designs were periodically modified. The earliest cobs featured a simple shield obverse and a cross with lions and castles in quadrants on the reverse, as seen on this Mexican cob:

This early 1600s Mexican cob clearly shows the standard early design. The obverse features the Habsburg shield, while the reverse has a Jerusalem cross with castles and lions in the quadrants. While the designs are clear, the strike is uneven, with the cross and date off-center.

Starting in 1607, some mints added the date to the legends, though it was often not visible on the crudely made cobs. Assayer initials were added starting in 1617 after the first Potosí debasement scandal. On this Bolivian 4 reales from 1658, the assayer initial E (Antonia de Ergueta) and the date 58 are visible:

While the overall design is clear, the cob is crudely shaped and the details are not well-struck, typical of Potosí cobs of this era.

In 1652, after a second major debasement scandal at Potosí, the mints replaced the cross design on the reverse of the cob with a new “pillars and waves” design that featured the Pillars of Hercules from the Spanish coat of arms, making Peruvian cobs easily distinguishable. Here is a Bolivian 4 reales from the 1653 with the pillars and waves:

The cob has bold full pillars-and-waves with bold date and denomination with 4 over rotated 4 full but partially doubled cross with bold second date below.

The Mexican mints continued using the old shield and cross design on coins like this 1700s 2 reales from Mexico City:

This Mexican cob, struck sometime between 1700-1730, shows how the overall style and design of Mexican cobs remained largely unchanged from the previous century. The shield and cross are well-detailed, but the strike is uneven and the planchet is typically crude. Some numismatic experts believe the continuation of this “old style” was due to a growing conservatism in the Spanish colonies, as well as the fact that the Mexican mints, unlike those in Peru, largely avoided major scandals and thus felt less pressure to change.

While most cobs were round (in theory if not always in practice), some Latin American mints produced “heart-shaped” cobs known as “corazon” like this crude Bolivian example from 1734:

The Bolivian “corazon” (heart) cobs are perhaps the most visually distinctive of all cob types. These “Royal” coins are probably associated with the Sacred Heart of Jesus, which started in France at the beginning of the 18th century and Philip V was devoted. It spread to South America, and therefore we can suppose that these coins were made as votive offerings of thanks or requests for favours to the Sacred Heart. This would explain the hole in the flan, possibly to be hung as a medal or sewn to a mantle. The dies used are the same as those of the “Royal” mintages. No more than 35 specimens of this “Heart Cut” type are known to exist, and no more than 3 examples minted in 1734 like the one that was offered in this auction are known.

The periodic modifications to cob designs, such as the introduction of the “pillars and waves” motif and the inclusion of assayer’s initials and dates, were more than mere aesthetic updates; they played a significant role in the competitive and interconnected world of early modern global trade. These changes were keenly observed by different markets, especially in regions like Asia, where the authenticity and silver content of cobs were of paramount importance. The introduction of distinctive designs helped cobs stand out in these international markets, reinforcing their reliability and value as currency. Moreover, these modifications influenced the minting practices of other colonial powers, who were compelled to enhance their coin designs to maintain the trust and usability of their currencies in global trade. This iterative process underscores how innovations in coinage often mirrored the dynamic and competitive nature of colonial economies, with each power seeking to ensure their currency remained a preferred medium of exchange in the complex tapestry of global commerce.

The end of the cob era and the transition to milled coinage In the 18th century, coin production technology advanced with equipment capable of producing perfectly round coins with lettered edges being imported from Europe. Milled coinage began to be produced at Spanish colonial mints from 1729-1747 (The transition occurred at different times in various mints throughout the Spanish Empire, with some continuing to produce cobs alongside milled coins until the late 18th century), as seen in the milled edges and more uniform shape of this Peruvian 2 reales from 1778:

This 1 real Royal (galano) Lima coin, while still somewhat crude, shows the transition towards more uniform, mechanically produced coinage in the mid-18th century. The overall shape is rounder. However, the design remains the same, with the pillars and waves motif on the reverse.

The transition to milled coinage was a gradual process that overlapped with the ongoing production of cobs. Milled coins were introduced as a more sophisticated and secure option, but most mints continued to simultaneously produce cobs into the 1750s-1770s due to their practicality and the existing infrastructure. Potosí was the final holdout, not fully ceasing cob production until 1773.

This 1770 Potosí 8 reales is one of the last silver cobs ever produced. While the edge is more uniform and the details (assayer initial, date, denomination) are clearer than on earlier cobs, the overall shape is still crude and the strike is somewhat uneven. This coin represents the last gasp of the cob style before it was fully replaced by machine-struck coinage.

The end of the cob era was largely driven by a need to combat the crude appearance and inconsistencies of cobs that facilitated counterfeiting and shaving. The shift to milled coinage with lettered edges coincided with Spain introducing new monetary regulations and weight standards in the early-mid 1700s. Ironically, just as the Spanish Empire reached its peak and the cob had gained global acceptance, technology and economic needs rendered the cob obsolete.

The legacy of the cob design in Latin America Although the Spanish Empire ceased producing cobs in the 18th century, the cob design persisted in some parts of Latin America well into the 19th century after independence. These coins, while not actual Spanish colonial cobs, show how the iconic cob design endured.

For example, this 2 reales “cob” from the Argentine Tucumán province was struck from 1820-1821, after Argentina gained independence:

This Tucumán “cob” has the crude shape and basic design elements of a Spanish colonial cob, with a simple shield on the obverse and a cross with castles and lions on the reverse. However, the legends proclaim “Tucumán Libre” (Free Tucumán) and the date range (820-24), asserting the province’s newfound independence. The choice of the cob style likely reflects both a lack of more advanced minting technology and a desire to maintain a familiar coin design in the tumultuous post-independence period.

Similarly, these Costa Rican 2 reales from the 1840s, while struck on machines, still bear the overall appearance of a cob with a crude, uneven shape and simple design:

These Costa Rican coins, struck over two decades after independence from Spain, show how the cob style persisted even as minting technology improved. While the edge is reeded and the coins are more uniform than old Spanish cobs, the design is still very simple and the overall quality is crude. Interestingly, these coins bear the initials “C.R.” for “Costa Rica,” but retain the old Spanish denomination “2 R” for “2 reales.”

Honduras also produced 2 reales coins in the early 19th century that were cob-like in appearance, such as this piece dated 1831:

This Honduran coin, while more uniform than the Costa Rican examples, still has a very basic design reminiscent of cobs. The obverse features a tree (possibly representing the famed mahogany forests of Honduras) surrounded by the legend “Estado Libre de Honduras” (Free State of Honduras), while the reverse has the denomination “2” flanked by patterns that evoke the old Spanish castles and lions.

The Venezuelan province of Barinas issued 2 reales in 1817-1824 during Venezuela’s war for independence that had the look of a cob:

This coin has been minted from 1817 to 1824 by General Jose Antonio Paez in the west-central south Venezuela in Caujaral, commonly known El Yagual, sited in the province of Barinas. The striking quality and shape are very similar to old Spanish cobs, reflecting the challenges faced by the newly independent Latin American states in establishing their own coinage.

These post-colonial Latin American “cobs” demonstrate how the Spanish cob design left a lasting impression on coinage in the New World. The persistence of the cob style shows how, even after independence, Latin American mints initially struggled with the same technical limitations and challenges of producing coins that the colonial Spanish mints faced. The cob was a simple design well-suited to cruder minting techniques. In a sense, the cob design became a symbol of Latin American economic independence and transition. Its use also reflected cultural continuity and economic pragmatism, as these newly independent states sought to maintain a familiar medium of exchange during tumultuous times.

The story of the Spanish cob is a fascinating tale of economic imperialism, technological limitation, and global trade. From their crude beginnings in the 16th century to their heyday as world currency in the 17th and early 18th centuries, to their persistence in Latin America after independence, cobs left an indelible mark on the history of money.

As the first truly global currency, cobs were the “world money” of their era, with a two-and-a-half century span that tells the story of the rise and fall of the Spanish Empire and its lasting influence. The cob’s story also parallels the broader evolution of money – from crudely made coins valued primarily by weight and metal content to more sophisticated, consistently made coinage where the issuing authority’s stamp provides the value.

The cob’s crude yet iconic appearance also tells a deeper story. The visually striking cobs of Potosí and Lima, with their uneven surfaces and incomplete designs, are tangible remnants of the immense human cost of the Spanish colonial enterprise as the story of cob coinage is deeply intertwined with the economic and social history of Spain and its colonies. The massive inflow of silver from the New World had profound economic impacts, notably the phenomenon known as the ‘Price Revolution’, which saw a general rise in prices throughout Europe due to the influx of precious metals. This period of economic upheaval had significant social consequences, affecting everything from the wealth of nations to the daily lives of ordinary people. In Spain and its colonies, the silver boom fueled an era of extravagant wealth and imperial expansion, but it also led to disparities in wealth distribution and contributed to economic conditions that would later challenge Spain’s dominance. The human cost of this wealth was staggering, with the mines of Potosí becoming synonymous with brutal working conditions for the indigenous and African laborers. The demand for silver spurred a demographic catastrophe among these populations, an aspect of the cob’s legacy that is often overshadowed by their numismatic appeal. This dark side of the cob coinage story reminds us that the coins were not just economic tools or collectors’ items; they were products of a colonial system that extracted tremendous wealth at an immense human cost. Understanding this broader historical context enriches our appreciation of cobs, providing a more comprehensive view of their significance in world history beyond their tangible value.

Today, cobs and cob-inspired coins are avidly collected for their historical importance and unique appearance. Their crudeness, once a sign of haste and imperfection, is now cherished as a window into the past. Each cob is unique, with its own story of production, circulation, and survival. For the numismatist, holding a centuries-old Spanish or Latin American cob is a tangible connection to a bygone era and a reminder of the enduring power and allure of silver and gold.

In the end, the story of the Spanish cob is a story of empire, economics, and the eternal human fascination with precious metals. It is a story that continues to captivate collectors and historians alike, offering a glimpse into a pivotal chapter in world history through the lens of numismatics.

If you enjoy collecting cob’s then you should read Daniel and Fred Sedwick’s book “The Practical Book of Cobs” and read Notre Dame’s page on Spanish Silver.

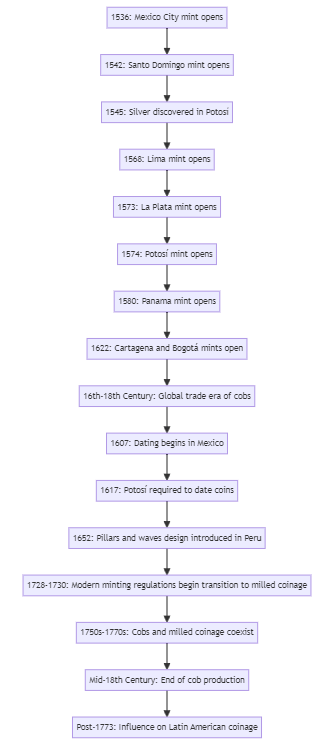

Timeline:

Leave a reply to ahrayahalvarran89 Cancel reply